Episode 079: Courage to have the Tough Conversations in the COVID-19 Pandemic

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Lauren Geoffrion BS, Dr. Timothy McNaughton, David Puder, MD

There are no conflicts of interest for this episode.

Our Time: COVID-19 And The American Culture:

With the reality of COVID-19 touching nearly every corner of the world, death and mortality is on our minds more than ever. Some cities have been deemed hot-spots. Death has claimed at least one person in everyone’s network of community. Some aren’t sick, but are simply standing by, waiting to see if the tsunami of disease will maintain enough inertia to impact their livelihoods as well.

I cannot speak definitively about the population of the world, but in the US, people do not talk about death often, or even acknowledge their own mortality. Instead, we act as if we just work hard enough (to find a cure, to earn enough, to prepare enough) we can do anything, even refuse the grim reaper. But with constant news of the novel coronavirus and the looming fear of running out of supplies (as many have) we are thinking more about death and having to have conversations around it.

The truth is, COVID-19 (in the US) is projected to kill about the same number of people as influenza did in 2017/18. We should be having conversations about death often. We are all humans who live, humans who die. The topic shouldn’t be corralled to times of pandemic. We are so averse to admitting our mortality that we would rather “fight” a disease with every possible intervention to hopefully give ourselves or our loved ones a few more weeks or months, even though it is often only an extension of suffering.

As physicians, we are familiar with the tragic picture of a patient who has been in and out of the ICU for 6 months or more, fighting to live, but who ought really to be allowed to pass with peace and as much dignity as possible. This is possible with palliative care or hospice. It is possible with acceptance. Then the focus becomes helping the patient live how they would like to—with the least amount of pain and suffering, until death occurs naturally.

What Is Palliative Care? What Is Hospice?

Palliative Care is “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering (World Health Organization).” The WHO gives a list of goals for palliative care:

provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

intends neither to hasten or postpone death

integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care

offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death

offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient's illness and in their own bereavement

uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling, if indicated

will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness

is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications

Hospice is defined by the Hospice Foundation of America as “care to help someone with a terminal illness live as well as possible for as long as possible, increasing quality of life...Care addresses symptom management, coordination of care, communication and decision making, clarification of goals of care, and quality of life”. A list of services include:

Time and services of the care team, including visits to the patient’s location by the hospice physician, nurse, medical social worker, home-health aide and chaplain/spiritual adviser

Medication for symptom control or pain relief

Medical equipment like wheelchairs or walkers and medical supplies like bandages and catheters

Physical and occupational therapy

Speech-language pathology services

Dietary counseling

Any other Medicare-covered services needed to manage pain and other symptoms related to the terminal illness, as recommended by the hospice team

Short-term inpatient care (e.g. when adequate pain and symptom management cannot be achieved in the home setting)

Short-term respite care (e.g. temporary relief from caregiving to avoid or address “caregiver burnout”)

Grief and loss counseling for patient and loved ones

Doctor’s Recommendation?

Not all of America pushes for every last intervention. In an essay written in 2016, (and since recirculated in several formats) Murray reveals that doctors do not die like everyone else. As a whole, doctors tend to refuse life-prolonging care like chemotherapy, life-support, being on a ventilator, and are the first to sign Do Not Resuscitate orders. Why is this? He writes that it is largely because doctors have seen and understood the futility of much of the aggressive treatment patients tend to receive at the end of their lives. It is also usually more painful, uncomfortable, unfamiliar, and PTSD and delirium-inducing for patients who are in an ICU level of care for long periods of time—especially for those who are older or with an extensive baggage of long-existing medical problems.

Doctors tend to choose hospice for themselves and for their family members because they’ve seen the patients in the ICU suffering and dying for long periods of time. They don’t want to be that patient. They want to be home with family, or in a location they love, and die in peace, not fighting the inevitable.

Interestingly enough, on average, patients that choose hospice live longer on average than their peers who choose aggressive treatment, even though they had similar prognosis and the same diseases at the start. This is counter-intutive, but is best understood by realizing that aggressive care plans may indeed deliver longer lives for some of the patients who choose them but many others have their lives shortened because of adverse effects associated with aggressive care measures.

So why do we keep treating people if even physicians don’t think it’s the best choice? Mixed up in a culture that emphasizes patient autonomy and criticizes with lawsuits, physicians often end up acting in a way that protects them from scrutiny. Unfortunately, this often leads patients or their families to make decisions on things they do not fully understand. If more physicians took the time to discuss a patient’s expectations or wishes for the end of their life, perhaps there would be less suffering for many people at the end of their lives. Murray (2016)

End Of Life Conversations:

Starting a conversation about end-of-life can be daunting in our death-denying culture. Whether dying of COVID-19 or another life-threatening illness, physicians need to be the ones initiating the conversations. However, these cannot be the just-stop-in-on-my-way-to-lunch conversations that require little forethought and limited word choice.

Patients cannot be expected to understand their total prognosis. This proceeds from the lack of experience with ICU care and aggressive interventions, lack of understanding their likely course based on their comorbidities and how their treatment course has gone so far. Rather than simply accepting the patient or family member’s admonition to “do everything,” a conversation is warranted to assess their understanding of “do everything.” Often, what they really mean, is “do everything that can help,” and it is up to the clinician to make that assessment and take the time to guide the family through those decisions with full disclosure.

Two things are especially important. First - clinicians should not leave the patient or family with the impression that their care is being limited, or that anyone is “giving up.” Although the goals of the care plan may change from life-extension at all costs to maximization of comfort and quality of life, the patient and family need never be left feeling that the best care is being denied them or that they will be left unsupported. It can be very helpful to emphasize that the care team will always do everything that can help the patient maximize their goals. Secondly - it is crucial for the clinician (and not the patient or family) to design care plans that make sense clinically given the patients underlying disease process and thereby protect patients from the responsibility of selecting specific treatments. Just as it makes no sense for a physician to seek a patient’s opinion regarding antibiotic therapy for Congestive Heart Failure, or to select between Norepinephrine and Dobutamine, it makes no sense for a physician to offer the choice of chest compressions when CPR is not indicated. Too often physicians feel pressured to do futile interventions by families that demand “everything” when it is the job of the clinician to restrict the therapeutic choices to those that make sense.

With limited time (especially in a crisis), be prepared for the discussion with a framework, and have certain phrases in mind that convey care and sensitivity to the family’s confused and grieving state. Clinicians must not place the family in the position of feeling responsible for ending their loved one’s life. By restricting the number of choices the family has to make, the physician can eliminate the guilt that could follow a family’s decision to transition from curative to comforting care.

SETTING UP THE CONVERSATION:

Use a team approach between multiple disciplines who have been tending to the patient. You can share the emotional burden of heavy conversations and have better communication between team members. Be well-informed before initiating the conversation, using the “who, what, when, where, and how” approach. Pfeifer and Head (2018)

Who: Ask the patient who they want present for the conversations

What: Clinicians should have a goal in mind

Ex: delivering serious news, clarifying prognosis/treatment, establishing goals of care, or communicating the patients goals and wishes for end of life to those in attendance

Discussion of prognosis is important, but should be based on patient preference for how in depth one goes

When: Meetings need to be scheduled. When squeezed in between activities, they are often incomplete, must be repeated, and ground is usually lost.

Where: Ideally, a quiet room without interruptions, but if at bedside, the clinician must at least sit down somewhere to show the patient his care and that he has time.

How: Semi-structured conversation is best, communication should be adapted based on acceptability to the patient

Avoid taking charge of the conversation

Listen first

Ask open-ended questions

Give intentional silence when needed

Acknowledge emotions and normalize their feelings

Be confident, direct, and calm—this is comforting

Remember, “patients might remember about 20% of what is said in the first serious illness or end of life discussion because their minds are reeling with emotions, impairing their memory”

Avoid post-conversation hallway conversations with family and friends. If necessary, return to the room with everyone to address questions so that all information is conveyed directly

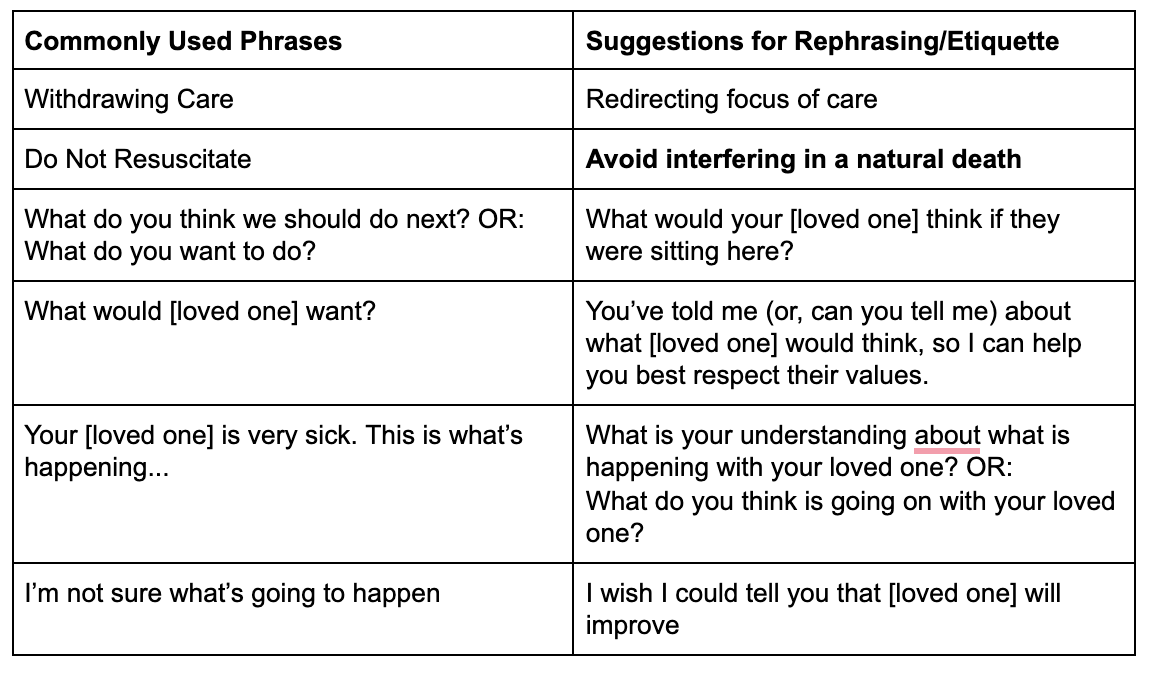

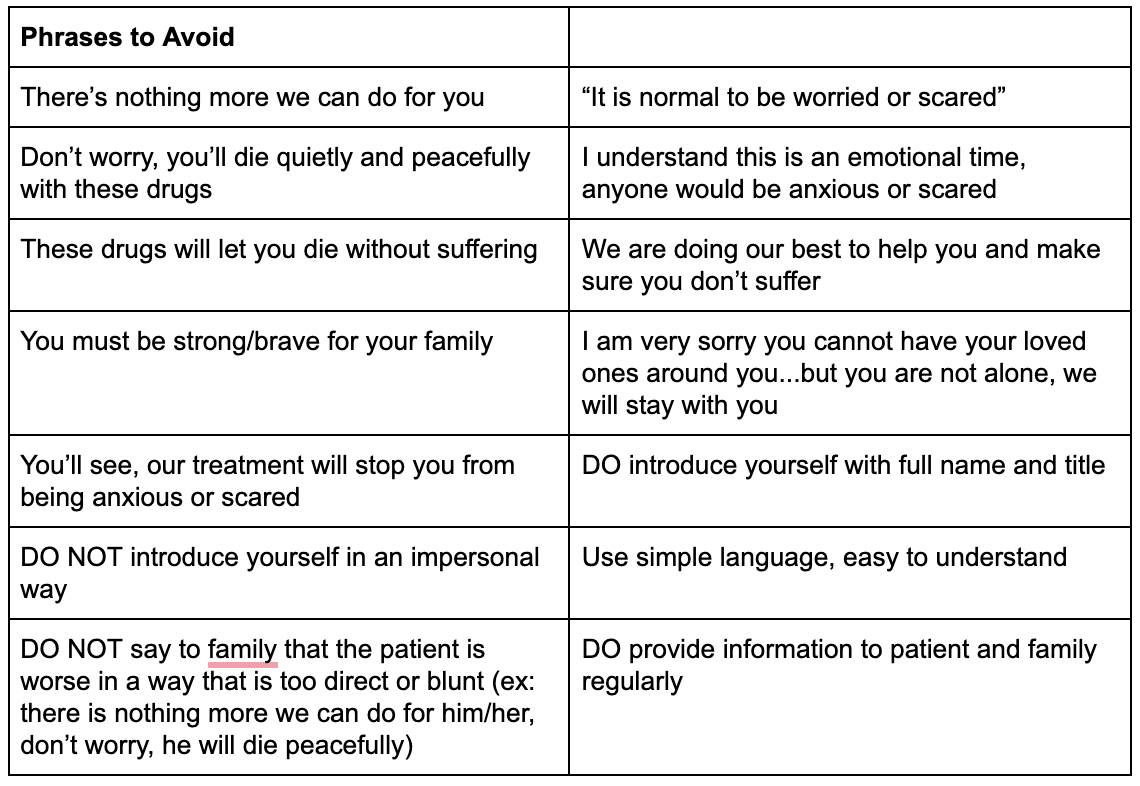

USING COMPASSIONATE AND SENSITIVE LANGUAGE:

Be sensitive to how the patient and family might feel about suggesting comfort care rather than curative care. They may feel like they are “giving up” or “failing” their loved one, so it is important to convey that palliative/hospice care is neither. Additionally, common language about making decisions for treatment insinuates that the physician is the gatekeeper of death, and that if only they choose to do one thing or another the patient will be guaranteed survival. However, we physicians do not hold the key, and in most cases, the patient will continue to die despite aggressive interventions, but perhaps a little slower. It is important to redirect the family’s focus in a compassionate way, acknowledging their distress, and guiding them toward making the decision that is best for their loved one.

WORD CHOICE FOR PATIENT AND FAMILY DISCUSSIONS:

Source: Italian Society of Palliative Care, Rhoads (2019)

Making Difficult Decisions:

During this pandemic, and in historical times of medical crisis, some people have been “forced” into palliative or hospice care. They are denied life-saving medical resources so that the limited amount of resources can be given to those with the best chance of survival. Making these decisions puts an unthinkable burden on the physician, so how are these decisions made? How are hospitals deciding who gets to be on the waiting list for a ventilator and who will be given supportive care? Thankfully, there are a number of guidelines and a code of ethics that have been published to relieve some of the burden of decision making from the physicians giving immediate care.

Ethical principles guiding decision making:

Stewardship of resources: duty to plan, triage allocation plan, specificity, duty to recover and restore

Duty to care: not to abandon, despite risks, to provide comfort care

Soundness: effectiveness, priority, non-diversion, information, appropriateness, risk assessment, flexibility

Fairness: consistent criteria, justice in decision making (impermissible factors are: race, gender, ethnicity, religion, social status, location, education, income, ability to pay, disability unrelated to prognosis, immigration status, or sexual orientation), medical need and prognosis

Reciprocity: protections of individuals, protections for essential personnel, protections for essential providers

Proportionality: balancing obligations, limited application and duration (restrictive measures), well-targeted restrive measures, privacy of decision makers

Transparency, veracity, and trust: public engagement, openness of all public health decisions, communication systems for decision makers, documentation, full disclosure for emergency responders, accessibility for all ages/disabilities/languages as much as possible

Accountability: individual responsibility for compliance or noncompliance with orders/recommendations, duty to evaluate, public accountability

Beneficence: duty to preserve the welfare of others

Respect for persons: individual autonomy, privacy, dignity, and bodily integrity must be upheld

Solidarity: binds the community that we are “all in this circumstance together”

Sources: Arizona, Louisiana, Michigan New York Kansas Washington Rapid Expert Consultation | Rapid Expert Consultation on Crisis Standards of Care for the COVID-19 Pandemic (March 28, 2020)

Allocation guidelines:

In considering who should or shouldn’t receive aggressive care (ex: being put on a ventilator) in the setting of limited resources, it is recommended that patients be evaluated and assigned a priority score. In the case that two patients have the same priority score, both should be given a fair chance via lottery or another randomization method to determine who receives the limited resource. In order to reduce strain on the physician giving the care, allocation decisions are to be made by a triage team and then put into place by the care-giving physicians. Those with the lowest priority scores after each category is added together are given higher priority on a waiting list. Though priority may be assigned differently on a per hospital basis, an example of priority score assignment criteria is listed below (Biddison 2019):

Prospects for short-term survival: whether or not a patient is likely to survive the aggressive interventions offered. Mortality over the short term can usually be estimated with reasonable accuracy using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score for adults and the Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction 2 (PELOD-2) score for children.

1 point for SOFA ≤ 8 or PELOD-2 ≤ 12

2 points for SOFA 9-11 or PELOD-2 12-13

3 points for SOFA 12-14 or PELOD-2 14-16

4 points for SOFA >14 or PELOD-2 ≥ 17

Prospects for long-term survival: this considers patients’ comorbidities. However, too much emphasis on prospects for long-term survival in age-matched individuals can further disadvantage people who already face systematic disadvantages. In order to minimize compounding injustices, this scoring assessment only takes into account patients whose comorbidities are so severe that they are expected to live no more than 12 months even with successful ICU treatment.

0 points for no severe comorbidities

3 points for severe comorbid conditions; death within 1 year

Ex: NYHA class 1 heart failure, advanced lung disease (with FEV1 < 25% predicted, TLC <60% predicted, or baseline Pao2 < 55mmHg), primary pulmonary hypertension with NYHA class III or IV heart failure, chronic liver disease with Child-Pugh score > 7, severe trauma, advanced untreatable neuromuscular disease, metastatic malignant disease or high-grade primary brain tumors

Special Considerations: Though ethically challenging, in some situations stage of life, pregnancy status, or other special circumstances may be considered in the decision-making process.

If necessary, points may be assigned based on age bracket of 0-49 years, 50-69 years, 70-84 years, or greater than 85 years

Exclusion Criteria: Cardiac arrest (unwitnessed, recurrent, or unresponsive to defibrillation or pacing), advanced burns in a patient with both age greater than 60 and more than 50% total body surface area affected

Psychological Effects of COVID-19

Both the disease and the national response to the COVID-19 pandemic present a threat to the psychological functioning of physicians, patients, and those self-quarantined for weeks, and possibly months to come.

One physician in Italy commented, “It is difficult to maintain the humanity of palliative care in this situation” (Costantini et al (March 2020)), and another, “Even if there is no chance,” he says, “you have to look a patient in the face and say, ‘All is well.’ And this lie destroys you.” Parodi (2020) Reuters.

It is easy to be worn out from so many emotionally charged conversations in the midst of witnessing so much death and illness. As healthcare providers, it is especially important to tend to your own mental health amidst the chaos that is felt in the hospital. For patients who are in isolation for weeks, or experiencing delirium from their illness, loneliness can easily precede depression or anxiety that must be tended to.

Even in those who never set foot in a hospital, but are quarantined with their families and housemates, we have already seen an increase in pathologies. Divorce rates and domestic violence police calls have increased markedly since quarantines began (Harvey 2020 and Prasso 2020). Decreased control of existing or subclinical anxiety and depression, drug use, and suicide are likely to accompany the trends we have seen with family dynamic issues.

Though there is an opportunity to grow closer and spend time strengthening familial relationships while at home, many people are not willing or not aware of the work necessary to heal and strengthen and default to strife. Recognizing the threat to the general population, in addition to healthcare workers, the World Health Organization published mental health and psychosocial considerations (here) in an effort to help minimize the risk of mental health issues that might follow the coronavirus tide.

In Summary

Physicians often decide to have less treatment than non physicians, and part of that is because we know what is actually reasonable, what might be considered excessive or unhelpful, and what “heroic” measures might actually be brutal.

“Doing everything” really means “doing everything that can help the patient ” As physicians, we need to be the ones leading the charge focusing on humanity, respecting the individual, how do we help this person suffer the least and transition with dignity, to death, if that is where they are going. Heroic Care can mean courageously accepting the limitations of our bodies in the face of overwhelming illness and choosing not to proceed with aggressive care measures.

Focus on handing patients back their humanity in the COVID-19 season, because the loneliness of the situation can be very dehumanizing

Bring meaning to the team by educating team members about the value of hospice and palliative care. Celebrate the transition to focusing on living well, and help shift the mindset by having these conversations.

If you are a healthcare worker who is struggling, please reach out to someone. Don't feel alone. Many psychiatrists and others are making extra room in their schedules to see and treat healthcare workers in these times.