Episode 100: The Big Five: Agreeableness

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.75 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Adriana Alvarez, BS, Ryan Holas, BS, Karl Wallenkampf, MA, Kyle Logan, BS, David Puder, MD

There are no conflicts of interest for this episode.

Facets of the Big Five

We are examining the facets of the most studied personality model, the Big Five. The facets are as follows:

Extraversion: the positive emotion dimension associated with gregariousness, charisma, enthusiasm, assertiveness, and social ability.

Neuroticism: negative emotionality associated with a proclivity to anxiety, anger, irritability, and emotional pain.

Openness to experience: the combination of interest and ideas are known as intellect. Associated interest in aesthetics. Enjoyment in ideas and spending time in creative pursuits.

Conscientiousness: central to orderliness and industrialism. A good predictor of long-term life success, especially in academic attainment. Focus energy on attention to detail and responsibility.

Agreeableness: compassion, politeness, maternal in orientation (those who often care about others more than themselves), cooperative more than competitive. Prone to be taken advantage of and harbor resentment (DeYoung et al. 2007).

Agreeableness has been mapped to the “more humane aspects of humanity,” contrasting a nurturing, caring, and emotional supporter with a hostile, indifferent, self-centered, spiteful, and jealous character on the other (McCrae & John, 1992, p. 196).

Notably, agreeableness should not be confused with extroversion. Rather, they are “orthogonal” (McCrae & John, 1992, p. 196), or at right angles to each other. For example, a person can be nurturing, caring, and emotional but low on extroversion (think about a kind introvert). Likewise, one can be self-centered, spiteful, and jealous, but also extroverted.

Today we are talking about agreeableness, which can be defined by looking at its six sub facets (A1-A6): trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, modesty, and tender-mindedness.

A1: Trust

Trust encompasses the belief that others are acting with good intentions (Costa et al. 1991).

A2: Straightforwardness

People high in straightforwardness are frank and direct. (Costa et al. 1991).

People who are high in straightforwardness will not be Machiavellian. They won’t try to manipulate people and what you see is what you get. But, those who are low in straightforwardness have more machiavellian traits. They are willing and able to manipulate people. They are capable of getting their needs met by moving people around like chess pieces.

As therapists, we want to be honest with our patients. Honesty can be felt on a mirror-neuron level in our brain. People know when you’re not being honest and if your words resonate with your internal experience, it gives weight to your words. Working through our own countertransference can allow us to be more authentically present and emotionally available in a meaningful way towards our patients.

A3: Altruism

Altruism describes characteristics of working for and intending the good of others (Costa et al. 1991).

I see most people in the mental health and medical fields leaning towards altruism. When burnout occurs the natural tendency towards altruism, intending good for others, has been sucked away. If you’re in the field and you’re wondering what happened to your initial desire to be helpful to others, you’re probably experiencing some burnout.

A4: Compliance

Compliance is the characteristic of individuals who submit to others during conflict instead of engaging in an outright contradiction or argument (Costa et al. 1991).

Someone who is high in compliance may not be a good negotiator because they may not stand up for themselves, which they might need to learn. If you look at low compliance it has some antisocial characteristics or psychopathic when it’s extreme.

A5: Modesty

Modesty comprises the spectrum of self-perception, ranging from people who pay little attention to themselves and their accomplishments to people who demonstrate extremely self-promoting views (Costa et al. 1991).

One of the strengths of low modesty is you may convince people of your accomplishments or better abilities than you actually have. A lot of success is the projection of success (Instagram is a perfect example of this). The advantage of being high in modesty is that people are more likely to desire companionship with you because of your cooperative nature and genuine humility.

A6: Tender-Mindedness

People high in tender-mindedness are more likely to make decisions based on sympathy for others. (Costa et al. 1991).

If you have justice and good economics you might be able to lift more people out of suffering. Justice is a big issue in our culture right now. How to increase justice for the most people possible is a very complicated question. Having a certain level of justice will create a society that can flourish, which will affect many people down the stream. Do you side with the person you can see in front of you or this ethereal idea? High ideation (high openness) will see how the ideas have the potential to lift people up on a more global level, while others really value the person in front of them more. But, if there is a person in front of you, empathy would be something valuable and necessary.

What is the difference between tender-mindedness and openness to feelings?

Openness to feelings is where you are able to notice what you feel in different situations. It’s being in touch with your own experience, whereas “tender-mindedness refers to the tendency to be guided by feelings; particularly those of sympathy and making judgments in forming attitudes.” Sympathy is ‘I feel sorry for someone else in their plight’ while empathy is ‘I see what this person is experiencing and I can relay that back to them.’ Our patients normally want empathy rather than sympathy.

When you’re analyzing different variables it can be difficult to answer questions. ‘How are you overall’ is the main key to these domains. Looking at the whole picture of how each variable flows together with your interpretation of the question or even your desired way of being plays into how you take the Big Five test.

Across the Lifespan

A 28-year prospective study with 194 participants examined childhood behaviors and agreeableness in adulthood. Personality and behavior data was collected at 8, 14, 33, and 36 years old. A few of the findings were compliance (r = .28), constructiveness (r = .18), and self-control (r = .26) at age 8 was predictive of agreeableness at age 33. High agreeableness in adulthood (age 33) was correlated with less alcoholism (r = -0.19, p < 0.01), less impulsivity (r = -0.24, p < 0.01), inhibited aggression (r = 0.30, p < 0.01), and increased socialization (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) at age 35 (Laursen et al., 2002).

“Table 1: Intercorrelations, internal Reliability, Means, Standard Deviations, and Sample Sizes” (Laursen et al., 2002)

The effect sizes on this are not that large. So, people do change a lot, but there does seem to be some link early on to what happens later in life.

Careers

Fittingly, agreeableness is positively associated with performance in service-oriented jobs.

“Figure 2. Effect of applicant-employee fit in agreeableness on organizational attractiveness Study 1)” (Van Hoye & Turban, 2015)

When applying to a job, the agreeableness of the employees there increases the attractiveness of working with that organization to someone highly agreeable. Whereas, to low agreeable applicants, the agreeableness of the employees marginally changed the attractiveness of the organization (Van Hoye & Turban, 2015).

Physicians in primary care, internal medicine, and hospital services scored higher in agreeableness than surgeons (Bexelius et al., 2016).

Higher agreeableness was associated with working in the private sector, specializing in general practice, and occupational health. Lower agreeableness and neuroticism were associated with specializing in surgery (Mullola et al., 2018).

Lee and Ohtake (2018) noted that agreeableness impacts people differently depending on the country and culture they are part of. Higher agreeableness is associated with higher income in male workers in Japan but is associated with lower income in male workers in the U.S. The effect was still significant even after controlling for variables such as occupation, industrial sector, and employment type. In the U.S. this is most strongly seen in smaller companies and disappears when looking at large companies. In contrast, the positive association of high agreeableness to higher income is strengthened at large companies (Lee & Ohtake, 2018).

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages

An advantage of high agreeableness is the exhibition of prosocial behavior or personality, which may lead to being good at de-escalating conflicts, gaining social capital, and fostering harmonious relationships.

Conflict resolution

Highly agreeable people strive for conflict resolution in a more peaceful manner, such as through negotiation tactics, whereas less agreeable people might use violence, aggression, or legal interventions (Graziano et al. 1996). A study done in 1996 had people rank common conflict resolution strategies in terms of effectiveness in specific conflict scenarios. These results showed that low agreeable men were more likely than high agreeable women to endorse power assertion tactics by an effect size of 0.78 (Table 2) (Graziano et al., 1996).

Basically, men who are low in agreeableness would use power assertion more frequently than women who are highly agreeable.

“Table 2: Study 1: Mean Levels of Endorsement Strategies by Sex and Agreeableness” (Graziano et al., 1996)

Advantages in social capital

High agreeable people may have more social capital than low agreeable people.

A study by Tulin et al. (2018) surveyed 1,069 people, then measured their instrumental social capital based on the socioeconomic resources they had access to in terms of social ties to different levels of social hierarchy. They also measured expressive social capital by using the De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (Tulin et al., 2018). Based on their results, agreeableness is positively associated with social support (B=0.25, SE=0.07, p=0.001) and thus expressive social capital. This may be because highly agreeable individuals show an increased commitment to others and the relationships they create, allowing them to build more trust and reciprocity in their relationships, and in turn be able to exchange their support for resources (Tulin et al., 2018).

I tend to see in my practice that it’s the highly disagreeable/low agreeableness males who oftentimes are devoid of friendship. The high agreeable females and males have a lot of friends, some of whom walk all over them. Some may have a semi-parasitic relationship, but they have a lot of friends. Often, highly disagreeable men or women focus on other aspects of their life. Especially if they’re high in conscientiousness they will focus on their work and spend most of their time at their job, because they prize getting ahead over gaining social capital. We know that friendships are life-giving and it’s the final common denominator that those with more severe mental illness have less meaningful relationships.

Disadvantages

Some of the disadvantages of being highly agreeable may be being prone to financial hardships, being taken advantage of, or getting involved in unbalanced relationships.

Disadvantages in finances

A study done by Matz & Gladstone (2020) found that of the Big Five personality traits, agreeableness was singularly related to unfavorable financial standing (Matz & Gladstone, 2020). This study found that people who score higher in agreeableness are:

Study 1: Moderately more likely to do cooperative negotiations (Beta: 0.38, p<0.001) (Figure 1).

Study 2: Less likely to value money, although it is a small effect size (Beta: -0.014, p =<0.001) (Figure 1).

Study 3: Slightly more likely to have debt (Beta: 0.10, p = 0.006) (Table 2).

Study 3: Slightly less likely to have savings (Beta: -0.15, p< 0.001) (Table 2).

Study 3: Slightly more likely to default (Beta: 0.09, p= 0.045) (Table 2).

This might be the case because of slightly lower income which is largely dependent on negotiation. The question comes down to what do you value more? You may be more willing to spend money on things that build more relational currency, but you may not be able to negotiate with your employer to get the kind of income that you deserve. This is why it's important to teach negotiation tactics in therapy to high agreeableness males and females. Teaching them how to have a voice, to put their needs out there, and how to use leverage can be crucial for career advancement for these people.

The financial effects are stronger in people with lower incomes (Matz & Gladstone, 2020). Also of interest from this study: high conscientiousness is more likely to have savings and less likely to have debt.

“Figure 1. Results of a Path Model Testing the Mediating Effect of ‘Importance of Money’ and ‘Cooperative Negotiation Style’ on the Relationship Between Agreeableness and Savings in Study 1” (Matz & Gladstone, 2020)

“Table 2. Results of Three Ordered Logistic Regression Models Predicting Savings (Left), Debt (Middle), and Default (Right) in Study 3” (Matz & Gladstone, 2020)

“Figure 3. Interaction Effects of Agreeableness and Income on Savings (top), Debt (middle), and Default (bottom) in Study 3” (Matz & Gladstone, 2020)

Agreeableness in a Relationship

Agreeableness in marital satisfaction

A study by Singh & Ahi (2014) took heterosexual married couples and had them rate their marital satisfaction, along with their own personality and their partner’s personality. The study found that actual personality similarity in agreeableness was positively correlated with marital satisfaction (r = 0.46) (Singh & Ahi, 2014).

“Table 1. (N=100) Correlations Between Actual Personality Similarity and Relationship Satisfaction Among Married Couples” (Singh & Ahi, 2014)

According to the Oxford Handbook of the Five-Factor Model, in terms of perceived compatibility: men low to average on agreeableness felt that they would be more compatible with a highly agreeable spouse, and men high in agreeableness felt that they would be more compatible with a less agreeable spouse. Whereas women felt most compatible with a highly agreeable spouse regardless of their own agreeableness levels (Widiger, 2017, pp. 431-432).

In this study, we see that women want high agreeable mates. They don’t always choose the high agreeable, but in a survey, they choose the high agreeable traits. There’s a thought in the involuntary celibates (INCEL) community that women really want a psychopath, but this proves that women do want high agreeableness even if they don’t know how to identify it.

Agreeableness in a Group Setting

A recent study by Wang et al. (2019) examined agreeableness and decision-making behavior in groups of healthy young adult males (n=60). Participants performed the balloon analog risk task (BART) alone and in pairs. Those with high agreeableness engaged in riskier behavior when making decisions in a group (correlation = 0.401, p<0.028) compared to making decisions alone. Participants with low agreeableness did not significantly change their decision-making behavior when in a group setting. More agreeable participants were also less affected by unexpected negative feedback (balloon explosion) when in a group setting. This was illustrated by their reduced P300 component using EEG studies (Wang et al. 2019).

“Figure B. Behavioral Result Average Pump Times” (Wang et al. 2019)

“Figure 5. Scatter Plots and Pearson Correlation Coefficient Analysis Results” (Wang et al. 2019)

This study seems to show that those who are highly agreeable tend to be swayed in a group more than people who are highly disagreeable. This may be why those who are highly disagreeable tend to rise as the leader of a group because they are willing to challenge people and push their thoughts out. There’s something about being in the group that makes agreeable people want to fall in line or adhere to the norms of the group, which leads to riskier behavior.

How Agreeable People Interact

Agreeableness, empathy, and fMRI

A study by Haas et al. (2015) looked at the association between agreeableness, empathic accuracy, and brain activity with fMRI in 50 healthy participants. People with higher agreeableness scores were better at recognizing emotions in other people compared to lower agreeableness people (r = .33, p = .02). The altruism facet of agreeableness was also associated with a better ability to recognize emotions in other people (r = .26, p < .05). High altruism scores were associated with increased brain activity in the left and right temporoparietal junction (TPJ) and medial prefrontal cortex (L. TPJ: r = .37; R. TPJ: r = .39; Med PFC: r = .45) (Haas et al., 2015).

“Fig 2. A. Results of the whole-brain analysis, within warm-altruistic composite scores predicting brain activity during emotional perspective-taking > shape matching” (Haas et al., 2015)

There’s more lighting up in the brain when you see other people's emotions, which leads to action for altruism. Altruism on this scale is similar to compassionate empathy. Compassionate empathy is moving into action to help someone else. There are people who are low agreeableness that are compassionate, which may have less to do with the suffering of an individual and more to do with the ideas of the best way to live.

Low agreeableness and anger

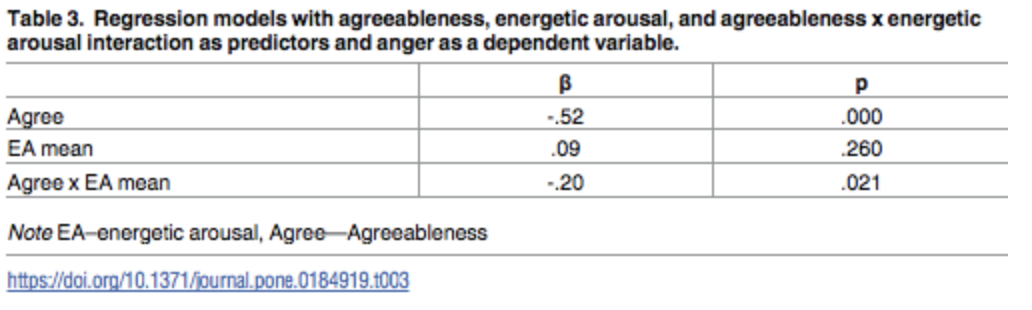

If you have a patient with low agreeableness scores, it may be prudent to be aware of their increased propensity toward anger and offer them tools for managing it. Anger is known to be associated with various adverse effects, including poorer health, relationship problems, and aggressiveness (Zajenkowski, 2017). In a series of four studies, Zajenkowski sought to understand the associations between agreeableness, energetic arousal, and anger.

Zajenkowski looked at the links among low agreeableness and high energetic arousal (measured by the Mood Adjective Check List), to trait anger (reported through the Aggression Questionnaire). He found that while anger and energetic arousal (EA) are not associated, and agreeableness and EA are linked, anger is significantly predicted by a low level of agreeableness combined with high EA (Zajenkowski, 2017).

“Table 1. Regression model with agreeableness, energetic arousal, and agreeableness x energetic arousal interaction as predictors and anger as a dependent variable” (Zajenkowski, 2017)

“Fig 1. Trait anger as a function of agreeableness and energetic arousal, study 1” (Zajenkowski, 2017)

Zajenkowski then showed the effect remained stable across a one-week study that measured mean EA, demonstrating that while high agreeableness individuals’ EA was not correlated with anger, whether high or low, low agreeableness and high EA were consistently associated with anger (Zajenkowski, 2017).

“Table 2. Correlations between anger, agreeableness, and energetic arousal” (Zajenkowski, 2017)

“Table 3. Regression models with agreeableness, energetic arousal, agreeableness x energetic arousal interaction as predictors and anger as a dependent variable” (Zajenkowski, 2017)

“Fig 2. Trait anger as a function of agreeableness and energetic arousal (the mean score from two measurements), study 2” (Zajenkowski, 2017)

Why are people low in agreeableness predisposed to anger in situations of high EA? This may be partially due to explanations of other authors cited by Zajenkowski, who argue that high-agreeableness individuals tend to focus on diminishing their angry and hostile emotions, possibly through bringing up emotionally positive thoughts in the face of anger. Zajenkowski speculates that individuals scoring low in agreeableness may not use cognitive strategies to minimize hostile thoughts, and therefore not combat the EA predisposition toward anger (Zajenkowski, 2017). We will address some opportunities for therapy later.

Pathologies in Agreeableness

Mortality associated with high agreeableness

Anger found in low agreeableness may be associated with poorer health outcomes, but is high agreeableness associated with any harm? A recent study indicated that high agreeableness may be associated with increased mortality. In a longitudinal study, Chapman and Elliot (2019) found an association between individuals of mortality who scored high in agreeableness having increased mortality. They report other studies that have shown this association using brief FFM assessments, as noted in Jokela et al. (2013). In their assessment, they looked specifically at the biennial General Social Survey (GSS). 1,461 adults from the GSS, selected in 2006, took the BFI-10, an extremely brief assessment of the FFM with only two items per domain. They found that those scoring one standard deviation above the mean in agreeableness had an increased mortality risk of 26%.

If the evidence is slim for agreeableness independently being linked to mortality in this study, is there any connection? In an earlier paper, Chapman et al. (2010) made an important association: high agreeableness conferred mortality risk in previous studies at low conscientiousness. They write, “this big 5 combination is denoted as the ‘well-intentioned’ style and is characterized by the pursuit of interpersonal harmony at the expense of one’s own diligence with respect to daily obligations and life goals” (Chapman et al., 2010, p. 7). They continue, “the quest for interpersonal harmony in the absence of self-discipline may signal a yielding to social pressures deleterious to health” (p. 7).

“Figure 2. Marginal probabilities of membership in the quintile of each ‘big 5’ dimension (agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, openness) across SES centiles, MIDUS Study, 1995-2004” in which SES= Socio-economic status, from (Chapman et al., 2010)

“Figure 4. Absolute risk of all-cause mortality over a 10-year-follow-up period from model 4 for different personality and SES risk-factor profiles” (Chapman et al. 2010)

You see a lot of high-agreeable family members who end up taking care of the whole family, and the other people in the family don’t have any boundaries with them. In their family structure, they’re the ones that are helping the sick family members a lot. This is where having boundaries and having a voice are important for high-agreeable people.

High agreeableness and dependent personality disorder

If high agreeableness combined with poor boundaries increases mortality, can it be linked with other problems? High agreeableness can be adaptive, but individuals may subsequently develop maladaptive behavior. Specifically, there are links between dependent personality disorder (DPD) and certain aspects of agreeableness traits (combined with aspects of neuroticism). Samuel and Gore (2012) argue that DPD is a “disorder of interpersonal relatedness defined by high agreeableness” (p. 1671).

We broke down each of our traits of agreeableness at the beginning of the episode. Specifically, the agreeableness traits of trust, altruism, compliance, and modesty can each become maladaptive and create dependent personality traits. For example, maladaptive trust can become gullibility, altruism may become self-sacrifice beyond reasonable levels, compliance may veer into submissiveness, and modesty may become overly meek (Samuel & Gore, 2012, p. 1679). DPD has been described by clinicians with a list of traits from the FFM using mostly traits associated with high agreeableness and neuroticism. Interestingly, the FFM historically tests for adaptive aspects of agreeableness, so when researchers changed test items to be maladaptive, e.g. changing “I try to be courteous to everyone I meet” to “I am overly courteous to everyone I meet,” the test markedly increased its associations between agreeableness and DMD (Samuel & Gore, 2012, p.1683).

They conclude that, though “instruments designed to assess general personality might lack fidelity for pathological extremes” (Samuel & Gore, 2012, p. 1688), there is remarkable value in finding maladaptive aspects of patients who score high in agreeableness through the FFM. This may allow therapists to identify individuals who could benefit from learning more adaptive traits and ways of placing boundaries around their agreeableness.

Everyone would want to say that they try to be courteous to everyone they meet. So, when people take these tests they will often answer questions based on who they want to be and not necessarily who they actually are. Compare that to being ‘overly courteous to everyone I meet.’ Maybe you don’t want to be overly courteous, but those who are highly agreeable, they would see themselves as overly courteous. Even people who are highly agreeable will have some resentments to that mentality. They know they are being walked over which builds up resentment over time, and it may have built up for years before they come into therapy.

Low in Agreeableness

Psychopathy vs secondary psychopathy

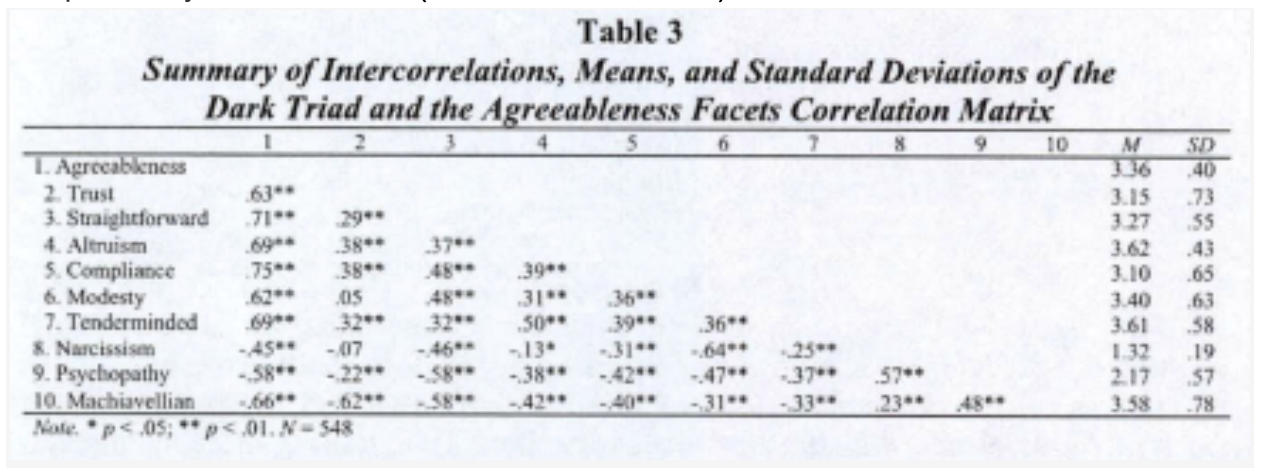

According to a study done by Stead and Fekken (2014), low agreeableness is associated with all three components of the Dark Triad: narcissism, psychopathy, and Machiavellianism, with emphasis on Machiavellianism. This study looked at the associations between the Dark Triad and interpersonally oriented traits. Agreeableness had negative associations with the following:

Narcissism: (r = -0.45, p < 0.01)

Psychopathy: (r = -0.58, p < 0.01)

Machiavelliansim: (r = -0.66, p < 0.01)

It’s not surprising that these traits are affiliated more with someone who is low trait agreeableness. Someone with high trait agreeableness is very relational and the dark triad’s fundamental issue is a lack of connection with other human beings. Narcissism is valuing yourself above other human beings or family members. What you can gain is more important than relationships with a narcissist. Psychopathy dehumanizes people, seeing them as insects. While Machiavellianism is the manipulative moving of people as though they were chess pieces.

Additionally, Machiavellianism had negative correlations with 5 of the 6 agreeableness facets: trust, straightforwardness, altruism, compliance, and tender-mindedness (all except modesty) (Table 3) (Stead & Fekken, 2014).

“Table 1. Summary of Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations of the Dark Triad and Interpersonally Oriented Traits” (Stead & Fekken, 2014)

“Table 3: Summary of Intercorrelations, Means, and Standard Deviations of the Dark Triad and the Agreeableness Facets Correlation Matrix” (Stead & Fekken, 2014)

Treatment

Helping those with high agreeableness

How can a therapist uniquely work with someone who is high or low in agreeableness? Ideally, we want to help high trait-agreeable individuals learn how to negotiate, stand up for themselves, and have boundaries.

According to Widiger and Presnall (2013), agreeableness is concerned with social and interpersonal relatedness. Thus, interpersonal models of therapy, such as marital-family and group therapy, are recommended for those who have maladaptively high agreeableness.

They discuss that maladaptively high-agreeable people commonly do not realize that it is their own traits causing distress, but will instead notice a pattern of problematic or abusive relationships in their history. In these patients, their meekness, self-sacrificing nature, and timidity should be properly addressed. Assertiveness training is beneficial alongside interpersonal methods and cognitive-behavioral therapy. There is no known pharmacotherapy that reduces agreeableness (Widiger & Presnall, 2013). Bucher et al. (2019) is a meta-analysis of 99 studies with N = 107,206, gives the following tips on therapy:

Working alliance displayed a strong association with agreeableness with r = .20.

The patient’s agreeableness was associated with favorable outcomes.

“Agreeableness (r = .10) had positive associations with symptom severity” (p. 57). So, higher levels of agreeableness were associated with fewer symptoms upon follow-up.

Agreeableness was more strongly related to overall favorable outcomes when treatment was 1-2 years, compared to 6-11 months or 4 weeks or less.

“Although an individual low in agreeableness might have poorer outcomes due to resistance and difficulty forming a therapeutic alliance, an individual high in agreeableness might overly focus on pleasing the therapist, in a way that impairs clinical progress” (p. 60).

Someone who is highly agreeable is more likely to have a good therapeutic alliance/working relationship. People with low agreeableness are a bit more tricky to form an alliance with. They’re open to an adversarial relationship where they will question and push you, which can be difficult for therapists. It takes time for someone who is highly agreeable to develop the ability to recognize their anger and get in touch with what their desires/needs are. They’re used to just reading other people and helping other people get their needs met. They spend their energy helping others feel good so that they can feel good through the positive emotions of other people.

A very common issue is the over-focus on the patient pleasing the therapist. What happens over time is that you’re not doing therapy for the patient, but more to make yourself feel. It also becomes an issue because the patient doesn’t learn how to get in touch with their own voice or desires. As a therapist working with someone who is high trait agreeableness, it’s going to be very hard for you to get them to tell you what they really think and you need to be ready to celebrate any small amount of frustration they share towards you, because that is the beginning of learning how to get in touch with their anger, needs, and make progress.

Nguyen et al. (2020) state, “whereas extraversion’s talkativeness and enthusiasm suggest an outward self-expression, agreeableness’s sympathy and harmony are more related to compliance” (p. 4). They continue on to say that, in the psychotherapy context, a tendency to speak one’s mind is perhaps much more beneficial than an inclination to avoid conflicts and disagreements.

Kushner et al. (2016) found that therapeutic alliance mediates the relationship between agreeableness and treatment outcomes in the context of MDD:

The reduction of depression severity is indirectly affected by high agreeableness via a patient-rated therapeutic alliance.

Interestingly, we observed divergent results across traits, such that in agreeableness, early ratings of alliance showed an increased reduction of depression severity while in extraversion and openness, reduction of depression severity was more related to late alliance, and “as such, agreeableness may have greater impact on the formation of alliance early on in treatment. In contrast, extraversion and openness may have greater bearing on the maintenance of alliance later in treatment” (p. 141).

Higher depression severity and neuroticism scores, and lower agreeableness scores were found in patients who prematurely terminated treatment.

Also, think about this as a moment for them to please the therapist. If they are asked for symptom scores, the highly agreeable person knows the therapist will be happy if they’re doing better which means it’s possible they’re doing worse than what they’re actually reporting.

Ramos-Grille et al. 2013 discuss how agreeableness predicts treatment outcomes in pathological gamblers:

“Individuals with lower scores on agreeableness may be less concerned with the effects of their gambling on others, in particular family members, and therefore they see the requirement of treatment as less important” (p. 603).

Low agreeableness seems to be a prognostic domain specifically for dropouts from treatment. An increase in the number of sessions of psychological treatments strongly emphasizing motivational enhancement and dropout prevention would benefit these individuals.

It’s harder to build a therapeutic alliance with low-level agreeable individuals, which leads to a higher dropout rate. Agreeable ones will find a therapist, get plugged in, and keep going. Whereas some of the disagreeable patients don’t really want therapy unless the therapist can challenge them and keep them captivated. One hurdle with low-agreeable people is getting them to believe in the process enough to keep going, which they don’t tend to desire because it’s paying for a relationship and they don’t place as high a value on relationships as highly agreeable patients will. But, if they can see they will gain something out of the sessions and move forward in their life, they may be more inclined to continue therapy.

Boundaries

Dr. Jordan Peterson discusses highly agreeable people and assertiveness in a Q&A streamed live on YouTube 6 August 2018 (Peterson 2018). In this video, he is asked what a woman who scores high in agreeableness can do to be more assertive. Peterson relates that people high in agreeableness can find themselves in a place of resentment because they spend so much effort tending to the needs of others. This resentment is caused by having something to say but don’t ask for the space to do so (Peterson, 2018, 0:11:24).

Peterson argues you must remember that you owe yourself as much as you owe other people. That, he says, is a moral duty. In the podcast, Ryan commented that this statement refers to a moral argument espoused by Immanuel Kant.

Kant argues we have a duty to promote our happiness in any situation because failing to do so might tempt us to violate other moral duties, and our happiness falls under the heading of our perfection. While moral duty may require us to sacrifice our happiness, sacrifice per se cannot be our universal law as the sacrificing of one’s own happiness for the sake of others would frustrate the happiness of all. Essentially, duties to oneself are not always about self-interest but about self-perfection and being worthy of one’s humanity (Hill, 2009).

If you are high in agreeableness, you are at risk of being taken advantage of and you must find a way to strategize yourself out of that. A key to doing so is to learn how to negotiate, which also means overcoming your hesitancy to engage in conflict. Negotiation and conflict are somewhat indistinguishable and it is easy moment-to-moment to avoid negotiation conflict, but you pay a terrible price for it in the medium to long term. It is better to face the conflict forthrightly in the present and make peace for the medium to long term, and there is courage in that (Peterson, 2018).

Dr. Puder in the podcast commented that a good practice for highly agreeable individuals with regards to conflict is to ask themselves if they can see themselves in a relationship with the other individual in 10 years if nothing changes, and a lot of the times the answer is ‘no.’

So, knowing that, how can we help them set up boundaries that could potentially allow the other person to change? In a work situation, how do you have boundaries with your work so they have the potential for them to value you enough so you don’t have resentment over the next 10 years? If you can’t make these choices now then you will not be in a relationship with these people later in life. Having a future perspective can allow you to make tough decisions now because of the value of relationships. If you are happy and content you will make a better partner, friend, and employee. Nobody wants to be in a relationship with someone who is resentful towards them.

Dr. Puder in the podcast explained the idea that high trait agreeable people are capable of reading others accurately and feel their intentions, yet they may feel bad about judging people. They want to believe the world is a good place and people think like themselves, which is why understanding toxic personalities (the dark triad) are crucial.

Assertiveness Training

Beginner’s Guide to Assertiveness Training:

https://www.therapyinmontreal.com/pdf/Assertiveness_Training.pdf

Help Low Agreeableness Develop Cognitive Empathy?

Cognitive empathy can be trained and can decrease aggressive solutions to conflicts. Perspective-taking was associated with increased problem solving (r = .32) and decreased verbal aggression (r = -0.32) during conflicts (Richardson et al. 1994).

It is absolutely possible to learn empathy. It is important to understand the internal motivations of people so that we can help them towards the right set of beliefs that will lead to a thriving society. The best way to win is to treat people well which is something someone with low agreeableness may need to start to believe by challenging alternative narratives.

We hope you follow along with us regarding all the episodes on personality! Let us know if you have any questions here.

Reference List

Ashton, M.C. and Lee, K. (2008), The HEXACO Model of Personality Structure and the Importance of the H Factor. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2: 1952-1962. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00134.x

Bexelius, T. S., Olsson, C., Järnbert-Pettersson, H., Parmskog, M., Ponzer, S., & Dahlin, M. (2016). Association between personality traits and future choice of specialisation among Swedish doctors: A cross-sectional study. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 92(1090), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133478

Bucher, M. A., Suzuki, T., & Samuel, D. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.002

Chapman, B.P., & Elliot, A.J. (2019). Brief report: How short is too short? An ultra-brief measure of the big-five personality domains implicates “agreeableness” as a risk for all-cause mortality. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(11), 1568–1573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317720819

Chapman, B.P., Fiscella, K., Kawachi, I., & Duberstein, P.R. (2010). Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the United States. American journal of epidemiology, 171(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp323

Conklin, Q. A., King, B. G., Zanesco, A. P., Lin, J., Hamidi, A. B., Pokorny, J. J., Álvarez-López, M. J., Cosín-Tomás, M., Huang, C., Kaliman, P., Epel, E. S., & Saron, C. D. (2018). Insight meditation and telomere biology: The effects of intensive retreat and the moderating role of personality. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 70, 233–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.03.003

Costa, P.T., Jr, & McCrae, R.R. (1995). Domains and facets: hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. Journal of personality assessment, 64(1), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6401_2

Crowe, M.L., Lynam, D.R., Miller, J.D. (2018). Uncovering the structure of agreeableness from self‐report measures. Journal of Personality. 86: 771-787. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12358

DeYoung, C.G., Quilty, L.C., & Peterson, J.B. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 880–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.880

Graziano, W.G., Jensen-Campbell, L.A., & Hair, E.C. (1996). Perceiving interpersonal conflict and reacting to it: The case for agreeableness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 820–835. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.4.820

Haas, B. W., Brook, M., Remillard, L., Ishak, A., Anderson, I. W., & Filkowski, M. M. (2015). I Know How You Feel: The Warm-Altruistic Personality Profile and the Empathic Brain. PLOS ONE, 10(3), e0120639. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120639

Hill, T.E., Jr. (2009). The Blackwell Guide to Kant’s Ethics. Wiley-Blackwell.

Hyatt, C. S., Sleep, C. E., Lamkin, J., Maples-Keller, J. L., Sedikides, C., Campbell, W. K., & Miller, J. D. (2018). Narcissism and self-esteem: A nomological network analysis. PLOS ONE, 13(8), e0201088. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201088

Jakobwitz, S., & Egan, V. (2006). The dark triad and normal personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2), 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.07.006

Jokela, M., Batty, G. D., Nyberg, S. T., Virtanen, M., Nabi, H., Singh-Manoux, A., & Kivimäki, M. (2013). Personality and all-cause mortality: individual-participant meta-analysis of 3,947 deaths in 76,150 adults. American journal of epidemiology, 178(5), 667–675. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt170

Jr, T. E. H. (2009). The Blackwell Guide to Kant’s Ethics. John Wiley & Sons.

Koorevaar, A. M. L., Hegeman, J. M., Lamers, F., Dhondt, A. D. F., Mast, R. C. van der, Stek, M. L., & Comijs, H. C. (2017). Big Five personality characteristics are associated with depression subtypes and symptom dimensions of depression in older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(12), e132–e140. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4670

Kushner, S. C., Quilty, L. C., Uliaszek, A. A., McBride, C., & Bagby, R. M. (2016). Therapeutic alliance mediates the association between personality and treatment outcome in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 201, 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.016

Laursen, B., Pulkkinen, L., & Adams, R. (2002). The antecedents and correlates of agreeableness in adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 38(4), 591–603. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.4.591

Lee, S. Y., & Ohtake, F. (2018). Is being agreeable a key to success or failure in the labor market? Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 49, 8–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjie.2018.01.003

Matz, S.C., & Gladstone, J.J. (2020). Nice guys finish last: When and why agreeableness is associated with economic hardship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(3), 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000220

McCrae, R.R., & John, O.P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 175–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x

Mullola, S., Hakulinen, C., Presseau, J., Gimeno Ruiz de Porras, D., Jokela, M., Hintsa, T., & Elovainio, M. (2018). Personality traits and career choices among physicians in Finland: Employment sector, clinical patient contact, specialty and change of specialty. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1155-9

Nair, D., Green, J. A., & Marra, C. A. (2020). Pharmacists of the future: What determines graduates’ desire to engage in patient-centred services? Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.030

Nguyen, P. L. L., Kim, H. L., Romain, A.-M. N., Tabani, S., & Chaplin, W. F. (2020). Personality change and personality as predictor of change in psychotherapy: A longitudinal study in a community mental health clinic. Journal of Research in Personality, 87, 103980. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103980

O’Connor, P. J., & Athota, V. S. (2013). The intervening role of Agreeableness in the relationship between Trait Emotional Intelligence and Machiavellianism: Reassessing the potential dark side of EI. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(7), 750–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.06.006

Peterson, Jordan. (2018, August 7). Q & A 2018 08 August A [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3VpxJg6jeMo&ab_channel=JordanBPeterson

Ramos-Grille, I., Gomà-i-Freixanet, M., Aragay, N., Valero, S., & Vallès, V. (2013). The role of personality in the prediction of treatment outcome in pathological gamblers: A follow-up study. Psychological Assessment, 25(2), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031930

Richardson, D. R., Hammock, G. S., Smith, S. M., Gardner, W., & Signo, M. (1994). Empathy as a Cognitive Inhibitor of Interpersonal Aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 20(4), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:4<275::AID-AB2480200402>3.0.CO;2-4

Samuel, D. B., & Gore, W. L. (2012). Maladaptive Variants of Conscientiousness and Agreeableness. Journal of Personality, 80(6), 1669–1696. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00770.x

Schaffhuser, K., Allemand, M. and Martin, M. (2014), Personality Traits and Relationship Satisfaction in Intimate Couples: Three Perspectives on Personality. Eur. J. Pers., 28: 120-133. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1948

Simms, L. J., & Watson, D. (2007). The construct validation approach to personality scale construction. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (p. 240–258). The Guilford Press.

Singh, S., & Makkar, A. (2014). Self and Partner Personality in Relationship Satisfaction. Indian Journal Of Health And Wellbeing, 5(12), 1483-1486. Retrieved from http://www.i-scholar.in/index.php/ijhw/article/view/88673

Soto, C.J., & John, O.P. (2009). Ten facet scales for the Big Five Inventory: Convergence with NEO PI-R facets, self-peer agreement, and discriminant validity. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(1), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.10.002

Stead, R., & Fekken, G. C. (2014). Agreeableness at the Core of the Dark Triad of Personality. Individual Differences Research, 12(4–A), 131–141.

Tulin, M., Lancee, B., & Volker, B. (2018). Personality and Social Capital. Social psychology quarterly, 81(4), 295–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0190272518804533

Wang, F., Wang, X., Wang, F., Gao, L., Rao, H., Pan, Y. (2019). Agreeableness modulates group member risky decision-making behavior and brain activity. Neuroimage 202: 116100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116100

Widiger, T. A., & Presnall, J. R. (2013). Clinical Application of the Five- Factor Model. Journal of Personality, 81(6), 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12004

Widiger, T. A. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of the Five Factor Model. Oxford University Press.

Van Hoye, G., & Turban, D. B. (2015). Applicant-Employee Fit in Personality: Testing predictions from similarity-attraction theory and trait activation theory. International Journal of Selection & Assessment, 23(3), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12109

Zajenkowski M. (2017). Hostile and energetic: Anger is predicted by low agreeableness and high energetic arousal. PloS one, 12(9), e0184919. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184919