Episode 098: The Big Five: Openness

By listening to this episode, you can earn 1.5 Psychiatry CME Credits.

Other Places to listen: iTunes, Spotify

Article Authors: Maddison Ulrich BS, Kyle Logan, BS, Matthew Hagele, MA, Mckinzie Johnson, BA, Alexis Carnduff BA, David Puder, MD

There are no conflicts of interest for this episode.

What Is Openness?

In this podcast, we discuss openness, the third of five in our podcast series looking at the domains within the Five Factor Model of personality. We look at how openness is defined, its heritability, and its effects on physical health, personal attributes, psychopathy, pharmacotherapy, and therapeutic techniques.

Openness can be defined by looking at its six subfacets (O1 - O6):

To add some specific examples, we decided to include our own results for openness from the NEO-PI-3. We use these results throughout the podcast to provide further discussion on how each facet of openness can present in real patients.

Openness Through Life

Childhood, adolescence, and young adults

It is important to know how the 5 personality traits change through different stages of life. People tend to have higher openness when they are younger and experience a steady decline as they age. One study “asked participants in 26 countries (N = 3,323) to rate typical adolescents, adults, and old persons in their own country. Raters across nations tended to share similar beliefs about different age groups; adolescents were seen as impulsive, rebellious, undisciplined, preferring excitement and novelty, whereas old people were consistently considered lower on impulsivity, activity, antagonism, and openness” (Chan et al., 2012). A series of studies involving participants 12-18 years old found growth in openness across boys and girls with no consistent changes in conscientiousness, extraversion, or agreeableness (McCrae et al., 2002).

Interestingly, different life events may affect our levels of openness as we age. One study observed that “exposure to childhood adversity was associated with an increase in levels of openness regardless of 5-HTTLPR genotype (P=0.001). Earlier studies have reported that childhood adversity was associated with higher openness to experience (Allen and Lauterbach, 2007, Hovens et al., 2016, Pos et al., 2016)” (Rahman, 2017).

Another study found that a person’s level of education also had an impact on openness. The study compared those who entered college with those who did vocational training. They found that the “initial level of openness was positively associated with college entry (r = .12, p < .01)” and remained higher throughout the study than in non-college participants. However, both educational tracks showed similar trajectories of increasing openness over time (Lüdtke, Roberts, Trautwein, and Nagy, 2011).

Middle age changes and influences

Looking further into adulthood, a longitudinal study found a partial decline in openness between the ages of 30 and 90 years old, with relative stability among the subfacets of fantasy, aesthetics, and ideas. Values, actions, and feelings showed a steeper decline over time (Terracciano, McCrae, Brant, & Costa, 2005).

Openness also seems to affect our choices in relationships and careers. When considering romantic partners, one study found that participants desired similarity in openness more than similarity in any other trait (Figueredo, Sefcek, & Jones, 2006).

Another study saw that “individuals with high openness to experience were less likely to get married and also postponed their first marriage.” They are also less likely to become parents and more likely to do so later in life (Jokela, Alvergne, Pollet, & Lummaa, 2011).

When considering career choices and the use of personality traits in career counseling, one study found that “higher scores on openness to experience are correlated with artistic and investigative occupations, while low scores on this scale are correlated with realistic and conventional occupations (Costa et al., 1984) on the [Social Desirability Scale] (SDS). Thus, congruence between results of interest or ability measures and these scales increase the likelihood that career choices in line with the personality assessment results will be effective choices. Occupational choices incongruent with this personality factor should engender further discussion of the reasons for these choices” (Hammond, 2001).

Genetics

Heritability

Another question asked about personality traits is whether or not they are heritable. There has not been extensive research into the heritability of openness, but we look into some of the results found so far. One study found “a significant heritability estimate for openness to experiences (P=0.005), with 21% of the variance between individuals explained by the genotyped common variants included in this study” (Power 2015). Interestingly, openness is the only Big-5 personality trait not associated with either sex.

Expression of Oxytocin

There does seem to be a correlation between openness and the expression of oxytocin. A recent study saw that “openness to experience was significantly associated with OXTR DNA methylation, while controlling for the remaining Big-5 personality dimensions (Neuroticism, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness) and sex and age (standardized β= −.232, t=2.72, p=.007). People that exhibit reduced OXTR DNA methylation (presumably associated with higher OXTR expression) tend to score higher on Openness to Experience. No other Big-5 personality trait was found to be significantly associated with OXTR DNA methylation” (Haas, 2018). Specifically, the study found that methylation was associated with the openness facets of actions (O4: r= −.60, p=.037), ideas (O5: r= −23, p=.006), and values (O6: r= −.17, p=.028). They did not find any association with fantasy, aesthetics, or feelings (Haas, 2018).

Twin Studies

The data does not show strong evidence for the heritability of openness in twins. A recent study found that “openness had no substantial genetic correlations with any PID-5-NBF dimension. The proportion of genetic risk factors shared in aggregate between the BFI traits and the PID-5-NBF dimensions was quite high for conscientiousness and neuroticism, relatively robust for extraversion and agreeableness, but quite low for openness” (Kendler, 2017).

Another study of the Big-5, looking at monozygotic (MZ) and dizygotic (DZ) twins in Canada found that openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness had significant changes in similarity of twins raised in different environments (Bergeman,1993). They found that (MZ) and (DZ) twins reared apart correlated .43 and .23, respectively, for openness. For MZ and DZ twins reared together, the correlations were slightly higher, finding .51 and .14 for openness. Total genetic influences estimated using model fitting techniques accounted for 40% of the variance for openness (Bergeman,1993).

Physical Health

Links to Weight

We also wanted to look at connections between openness and physical health. A meta-analysis from 9 cohort studies (n = 78,931) examined personality traits and how they related to the development of obesity. They found that “higher scores in openness to experience was associated with lower odds of obesity (pooled OR = 0.95; CI=0.91-0.99), but this association disappeared when adjusted for education (OR=0.99; CI=0.95-1.04). Some individual studies found significant associations with openness to experience and obesity but pooled OR was not significant. The only personality trait associated with lower obesity risk across studies was conscientiousness (pooled OR = 0.84; CI=0.80-0.88)” (Jokela et al., 2013).

A review of studies on personality traits and obesity from 2020 found a consistent association between healthy BMI and conscientiousness. Openness to experience had contradictory findings in relation to BMI and no significant effect (Chapman et al., 2020). An Australian study of 10,227 adults examined physical activity and physical exercise. Conscientiousness and openness (d=0.14) predicted subsequent increases in physical activity, whereas agreeableness predicted subsequent decreases in physical activity. (Allen, 2017)

Coronary Artery Disease

A study of 977 coronary catheterization patients with significant coronary artery disease did not find any association between the openness to experience as a domain in all-cause mortality or cardiac deaths. The study did find significant associations with some individual facets within openness to experience. Openness to feelings and openness to actions were associated with a 24% and 23% reduction in cardiac death risk and a 17% and 14% reduction in all-cause mortality risk, respectively. In addition, openness to aesthetics was protective against cardiac deaths with a 15% reduction in risk (Jonassaint et al., 2007).

Marijuana Use

Interestingly, a cross-sectional study of 300 college students found greater openness to experience and impulsivity were significantly associated with greater marijuana use within the last year, with OR of 1.13 and 1.05, respectively. Openness to experience was also associated with recent use (>1mo) with odds ratio of 1.08. This has been consistent with prior studies (Phillips, 2018).

This next study is unique in the literature because it compares university students with 62 chronic cannabis users and 45 cannabis-naive controls. On the NEO-FFI, users scored higher than controls on openness, but lower on agreeableness and conscientiousness. Follow-up ANOVAs revealed that the cannabis group scored higher than the control group on the openness scale [F(1, 105] = 11.57, p < 0.001; Cohen's d = 0.67], but lower on the agreeableness [F(1, 105) = 5.02, p < 0.05, d = 0.44] and conscientiousness [F(1, 105) = 18.71, p < 0.001, d = 0.85] scales (Fridberg, 2011).

Traits

Political Beliefs

It is commonly thought that levels of Openness to Experience precede conservatism with lower levels of Openness to Experience preceding higher levels of conservatism. The following study did not support this assumption. A recent study using nine annual waves of a nation-wide longitudinal panel study with 17,207 participants examined the “temporal ordering of Openness to Experience and conservatism” (Osborne, 2020). The study found the two traits develop in parallel with conservatism predicting decreases in Openness to Experience (effect size = -0.059) and Openness to Experience predicting conservatism (effect size = -0.096) (Osborne, 2020). The study, after controlling for between-person stability found that Openness to Experience and conservatism did not predict changes in each other over time.

Empathy

We also wondered if there was a link between levels of openness and empathy. However, the only study we found that answered that question found that empathy is associated with higher agreeableness, not openness (Konrath, 2018).

Love and Work

Another study looked at how openness levels affect work and love, finding that “those who experienced more pronounced increases in openness tended to delay romantic commitment, put less emphasis on extrinsic rewards such as salary, and had increased person‐job fit in midlife. At the facet level, intellectual interests were especially predictive of positive educational outcomes, while aesthetic interests and unconventionality predicted winding, autonomous career paths. We conclude that openness does matter in love and work. But, rather than stable levels of openness, the particular ways in which a person is open (intellectually, unconventionally, or artistically) and how their openness changes across emerging adulthood seem to be the factors most relevant to love and work outcomes” (Schwaba, 2019).

Abuse and life events

This next study assessed whether a history of abuse affected levels of openness. They also looked at links between openness and positive or negative life events. They found that “childhood abuse, openness to experiences and extraversion were significantly positively correlated with negative life events, and openness to experiences was significantly positively correlated with abuse” (Pos, 2016). They also found that, in general, “openness to experiences and extraversion were significantly positively correlated with positive life events.”

Academic performance

Another common assumption is that openness to experience relates to levels of education and intelligence. A recent study stated, “our own meta-analytic results indicate that only two of the six openness facets, namely ideas and values, are positively related to academic performance whereas the other four are not. Furthermore, on the intermediate level between dimension and facets, intellectual openness (reflected by the ideas facet) promoted academic performance, while senso-aesthetic openness (reflected by the fantasy, aesthetics, feelings, and actions facets) showed, in fact, a detrimental effect in our meta-analytic structural equation model” (Gatzka, 2018).

Psychopathology

Psychosis

One study suggests there may be a link between psychosis and openness. They looked at two networks in the brain: the default network (DN), which is the center for anything that requires the simulation of experience, rather than attention to current sensory input, and the frontoparietal control network (FPCN), which is the center for voluntary control of attention. Activity of the DN has been observed in patients with schizophrenia and in people at high risk for psychosis. The FPCN has primary nodes in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, lateral parietal cortex, and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, and has been shown to exhibit reduced functional connectivity in those with psychosis.

This study found that “Openness and psychoticism were associated with increased Default Network coherence and decreased Frontoparietal Control Network coherence, and their shared variance was associated with this pattern of coherence even more strongly. Intelligence showed a positive relation to Frontoparietal Control Network coherence and no relation to Default Network coherence. Controlling for intelligence did not eliminate the significant associations of coherence with Openness and psychoticism. These findings suggest that similar biological mechanisms may underlie psychosis-proneness across traditional indicators of risk and associated normal-range personality traits” (Blain, 2019).

They also found that “psychoticism was negatively related to Frontoparietal Control Network coherence (β = -.32, 95% CI [-.49, -.15]) but positively related to Default Network coherence (β = .25, 95% CI [.08, .42]). Similar results were seen for Openness, with Default Network coherence positively predicting Openness (β = .21, 95% CI [.08, .33]) and Frontoparietal Control Network coherence negatively predicting Openness (β = -.25, 95% CI [-.38, -.12]). These associations remained significant even after controlling for intelligence.”

This study suggests a link between schizophrenia and high openness. While high openness is usually seen as a desirable quality, extremely high openness might become pathologic and no longer beneficial.

Dementia

A recent study on possible treatments for dementia “tested whether diversity in activity helped to explain the overlap between openness to experience and cognitive functioning in an older adult sample (n = 476, mean age: 72.5 years). Results suggest that openness is a better predictor of activity diversity than of time spent engaged in activities or time spent in cognitively challenging activities. Further, activity diversity explained significant variance in the relationship between openness and cognitive ability for most constructs examined. This relationship did not vary with age, but differed as a function of education level, such that participating in a more diverse array of activities was most beneficial for those with less formal education. These results suggest that engagement with a diverse behavioral repertoire in late life may compensate for lack of early life resources” (Jackson, 2019). The results suggest that a person’s openness may be affected by their activities. Furthermore, the study hopes that attempting to increase a patient’s openness by assigning them to participate in a variety of activities may provide some protection against the development of dementia.

Anxiety

This next study assessed the relationship between openness and anxiety. They looked at college students, and questioned how openness played into their risk of developing anxiety after starting school. They found “that the stressful situation of entering the professional curriculum is marked by a combination of decreased openness to experience & increased extraversion in the great majority of normal students, and those with pure anxiety. In contrast, the co-morbid group has a relatively high prevalence of homebodies (decreased extraversion & openness) who like to spend most of their time alone. We hypothesize that an optimal balance of extraversion and openness to experience is essential for psychological resilience. Drastic decrease in openness (alexithymia) along with increased extraversion predisposes the subjects towards the development of anxiety symptoms, since by focusing more on the external world, they neglect attending to their internal capacity necessary for psychological resilience” (P, 2020). They also hypothesized that “a harmonious combination of extraversion and openness in optimal proportions is essential for psychological resilience. Regarding the etiology of depression and anxiety, the linear relation between neuroticism and low extraversion on one hand, and high extraversion and low openness on the other, links well to the hypothesis that anxiety and depression are polygenic disorders with a partly shared common genetic background.”

Autism Spectrum Disorder

There does seem to be an association between openness and the autism spectrum. A recent review found “a positive correlation between ASD (severity) and neuroticism and a negative correlation between ASD (severity) and extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness” (Vuijk, 2018).

Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

One of the more interesting correlations is between high openness and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. More research needs to be done, but the data may prove to be helpful in using personality traits for schizophrenia and bipolar risk assessment and treatment in the future. One study found that “high genetic correlations were found between openness and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder” (Lo, 2016).

Depression

There do seem to be some ties between openness and depression. One study looked at medical students to see if their personality traits could give insight into their risk of developing depression once school started. They found that “students with weaker adjustment personalities are more prone to develop psychological problems. This can have important policy implications in that students with weaker adjustment dimensions can and should be identified earlier and provided with additional system support to prevent stress and depression. Depression is also seen to be associated with openness (r = 0.241, P = 0.002) and agreeableness scores (r = 0.157, P = 0.047). Thus, students who are less adjusting, more open, and more agreeable also are likely to develop depression” (Goel, 2016). This could be very helpful in assessing individual students’ needs when they enter school, and providing them with better support to help them stay healthy and succeed.

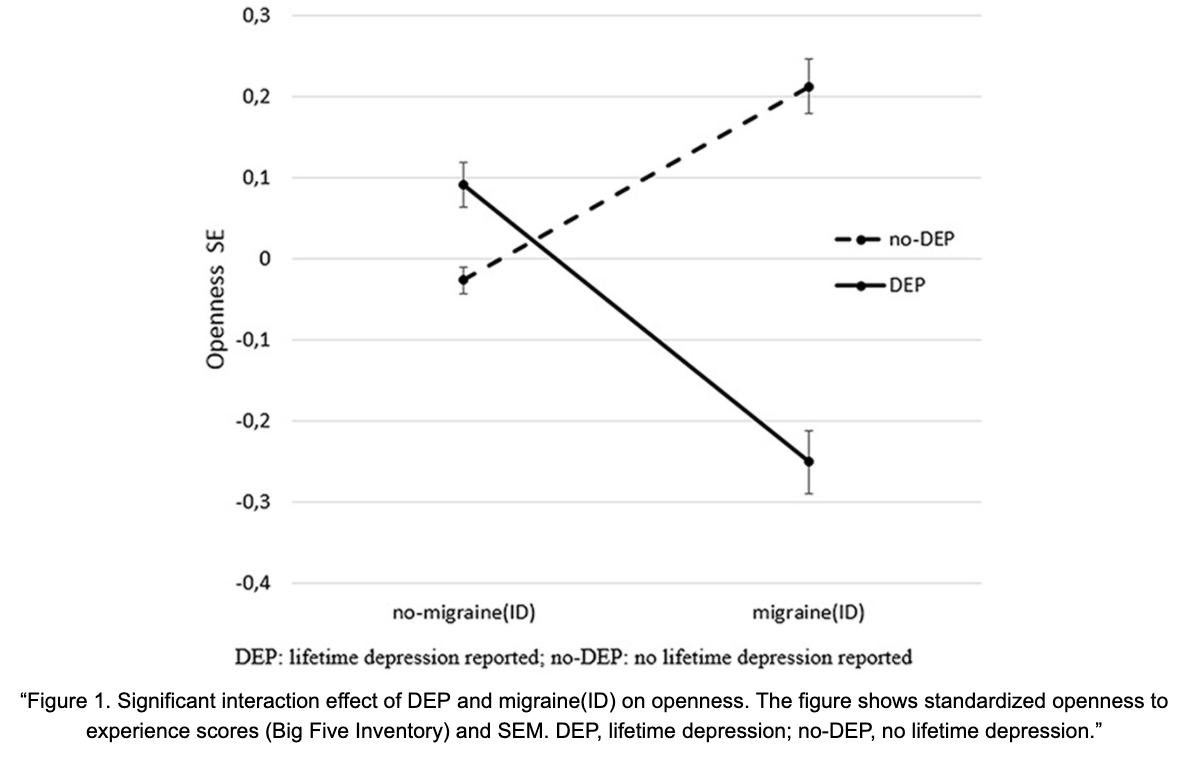

Another study looked at the connection between openness and patients with both depression and migraines. “While we confirmed previous results that high neuroticism is a risk factor for both depression and migraine, openness to experience was significantly lower in the co-occurrence of migraine and depression. Our results suggest that increased openness, possibly manifested in optimal or advantageous cognitive processing of pain experience in migraine may decrease the risk of co-occurrence of depression and migraine and thus may provide valuable insight for newer prevention and intervention approaches in the treatment of these conditions” (Magyar, 2017).

Another study looked at a possible link between lower levels of openness and treatment resistance in depression. “Many studies have reported that depressed patients show high neuroticism, low extraversion and low conscientiousness on the NEO (Neuroticism Extraversion Openness Five Factor Inventory). Our study highlights low openness on the NEO, as a risk mediator in treatment-resistant depression. This newly identified trait should be included as a risk factor in treatment-resistant depression” (Takahashi, 2013).

Pharmacotherapy

Depression treatment with ketamine

Another very interesting topic of research right now is how increasing openness through pharmacotherapy can influence the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions. One study from this year found that high openness significantly predicted a sustained treatment outcome when treating patients with treatment-resistant depression with long-term ketamine therapy (Dale, 2020). “After adjusting for age, sex, education, and initial MADRS score, the odds of being a sustained response rather than an intermediate response/no response were 3.36 times higher for patients with a high openness T-score, compared to patients with a low openness T-score (95% CI = 1.26 to 8.93, P = 0.015).” Using personality traits to screen patients for the likelihood of therapy success may prove to help make therapy decisions more targeted and effective.

MDMA

Another recent study looked at the role openness played in MDMA treatment effectiveness for PTSD. “Results indicated that changes in Openness but not Neuroticism played a moderating role in the relationship between reduced PTSD symptoms and MDMA treatment. Following MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, increased Openness and decreased Neuroticism when comparing baseline personality traits with long-term follow-up traits also were found. These preliminary findings suggest that the effect of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy extends beyond specific PTSD symptomatology and fundamentally alters personality structure, resulting in long-term persisting personality change” (Wagner, 2017).

Psychedelics

Yet another study comparing recreational drug users to controls showed that psychedelic use may actually change a person’s level of openness over time, and that there is a link between serotonin levels and openness. They stated that “of the five NEO-PI-R traits, only openness to experience scores differed between the three groups: psychedelic-preferring recreational users showing higher openness to experience scores when compared with both MDMA-preferring users and controls. Openness to experience scores were positively associated with lifetime number of psychedelic exposures, and among all MDMA-preferring user/psychedelic-preferring recreational user individuals, frontal serotonin transporter binding – but not frontal serotonin-2A-receptor binding – was positively associated with openness to experience. Our findings from this cross-sectional study support increasing evidence of a positive association between psychedelic experiences and openness to experience, and (a) expands this to the context of ‘recreational’ psychedelics use, and (b) links serotonergic neurotransmission to openness to experience. A modulation of personality induced by psychedelic experiences may have important therapeutic implications via its impact on peoples’ value systems, cognitive flexibility, and individual and social behaviour” (Erritzoe, 2019).

The study was able to look at the sub-facets of openness as well. Interestingly, “explorative analysis of the openness’ facets revealed that openness to values (1.0±0.3 increase in score per doubling in lifetime psychedelic exposure, p=0.009), openness to actions (1.0±0.3, p=0.010), and openness to ideas (1.2±0.5, p=0.013) showed significant positive associations with lifetime psychedelic use, openness to aesthetics showed a borderline association (1.1±0.6, p=0.087), whereas openness to feelings and fantasy were not associated (p=0.770 and p=0.782, respectively).”

Guiding Therapy

Changing a patient’s level of openness

One of our biggest questions is how knowing a person’s personality traits can help guide his/her therapy. This first study we chose to discuss looked at the influence of a patient’s degree of openness on cognitive ability. The ultimate goal of this study was to see if therapy can be used to influence a patient’s cognitive ability, and ultimately help decrease their risk of dementia. “The present study investigated whether an intervention aimed to increase cognitive ability in older adults also changes the personality trait of openness to experience. Older adults completed a 16-week program in inductive reasoning training supplemented by weekly crossword and Sudoku puzzles. Changes in openness to experience were modeled across four assessments over 30 weeks using latent growth curve models. Results indicate that participants in the intervention condition increased in the trait of openness compared to a waitlist control group. The study is one of the first to demonstrate that personality traits can change through non-psychopharmacological interventions” (Jackson, 2012).

Openness and therapeutic outcomes

This next study looked at how levels of openness related to therapeutic outcomes. They had both the therapists and the clients (54 total dyads) rate their traits at intake and through the therapeutic process to look for changes. Client-rated openness to experience at the 4th therapy session was predictive of symptom improvement with an effect size of 0.52. Clinician-rated openness to experience at the 4th therapy session was also predictive of symptom improvement with an effect size of 0.59 (Samuel, Bucher, & Suzuki, 2018).

A meta-analysis of 99 studies (N=107,206) asked how openness affected specific therapeutic outcomes. Openness to experience was positively correlated (r=.15) with client-reported working alliance. Patients “in treatment for one to two years had significantly stronger positive associations with openness to experience and overall outcome (r = .50) compared to those who were in treatment for 6 to 11 months (r = .06), one to five months (r = .004), and four weeks or less (r = −.12).” The data suggests that patients with high openness to experience benefit from therapy delivered over a greater time frame (Bucher, Suzuki, & Samuel, 2019).

A different study surveyed 38 psychotherapy practitioners to see what domains and facets of the Five Factor Model were the most important in helping or hindering the therapeutic alliance. They found that “high openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness are perceived as favourable to therapeutic alliance. While lower scores on these domains are perceived as unfavorable to therapeutic alliance” (Thiry, 2020).

Using personality traits to guide therapy

Personality traits can affect how patients present to therapy. Low openness patients may seem resistant to therapy and closed off, and it is important to not mistake this aspect of their personality as a judgement about their progress. “The psychoanalytic school implicitly demands the ability to fantasize and symbolize; failure to do so is regarded as resistance, which the therapist is expected to help the client overcome. (...) Therapists who understand the O domain will be less likely to make potentially harmful value judgements about such clients or themselves.” Conversely, high openness patients may seem healthier than they really are, due to their ability to symbolize and the fact that they are “more willing to try new ways of thinking or relating to others.” Personality will also have implications for treatment. Low openness patients may prefer behavior therapy or CBT, while high openness will be more willing to try more abstract types like gestalt, hypnotherapy, etc. Personality also affects outcome. Effectiveness of therapy may be difficult to measure due to countertransference of openness levels from therapist to patient. For example, a high openness therapist may see high openness patients as more responsive than low openness patients, as low openness patients will likely have a more difficult time expressing themselves. Similarly, knowing openness levels of both patients will help to provide more effective treatment when doing couples or family therapy (Miller, 1991).

Predicting response to therapy

Another study looked at interpretive versus supportive therapy in patients dealing with grief. They found that openness was associated with favorable treatment outcomes in both types of therapy. “We found a significant main effect for openness for the Target Objectives and Life Satisfaction outcome component (Fchange = 3.88, df = 1,100, p = .05).” Patients high on openness can be challenged and confronted with new ways of thinking, whereas patients low on openness, novelty may be frightening. (Ogrodniczuk, 2003)

Career counseling

A study on career counseling noted the importance of using personality traits to guide therapy. Clients scoring low in fantasy may prefer more structured jobs that lack the unexpected, with high-openness clients having difficulty committing to a career path due to their wide range of interests (Hammond, 2001).

Reference List

Allen, M. S., Magee, C. A., Vella, S. A., & Laborde, S. (2017). Bidirectional associations between personality and physical activity in adulthood. Health Psychology, 36(4), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000371

Bagby, R. M., Gralnick, T. M., Al‐Dajani, N., & Uliaszek, A. A. (2016). The Role of the Five‐Factor Model in Personality Assessment and Treatment Planning. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 23(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12175

Blain, S. D., Grazioplene, R. G., Ma, Y., & DeYoung, C. G. (2019). Toward a Neural Model of the Openness-Psychoticism Dimension: Functional Connectivity in the Default and Frontoparietal Control Networks. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(3), 540–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbz103

Bucher, M. A., Suzuki, T., & Samuel, D. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of personality traits and their associations with mental health treatment outcomes. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.002

Chan, W., Mccrae, R. R., De Fruyt, F., Jussim, L., Löckenhoff, C. E., De Bolle, M., Costa, P. T., Sutin, A. R., Realo, A., Allik, J., Nakazato, K., Shimonaka, Y., Hřebíčková, M., Graf, S., Yik, M., Brunner-Sciarra, M., De Figueroa, N. L., Schmidt, V., Ahn, C. K., Ahn, H. N., … Terracciano, A. (2012). Stereotypes of age differences in personality traits: universal and accurate?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 103(6), 1050–1066. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029712

Chapman, B. P., Elliot, A., Sutin, A., Terraciano, A., Zelinski, E., Schaie, W., Willis, S., & Hofer, S. (2020). Mortality Risk Associated With Personality Facets of the Big Five and Interpersonal Circumplex Across Three Aging Cohorts. Psychosomatic Medicine, 82(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0000000000000756

Dale, R. M., Bryant, K. A., Finnegan, N., Cromer, K., Thompson, N. R., Altinay, M., & Anand, A. (2020). The NEO-FFI domain of openness to experience moderates ketamine response in treatment resistant depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 323–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.010

Erritzoe, D., Smith, J., Fisher, P. M., Carhart-Harris, R., Frokjaer, V. G., & Knudsen, G. M. (2019). Recreational use of psychedelics is associated with elevated personality trait openness: Exploration of associations with brain serotonin markers. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 33(9), 1068–1075. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881119827891

Figueredo, A. J., Sefcek, J. A., & Jones, D. N. (2006). The ideal romantic partner personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(3), 431-441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.02.004

Fridberg, D. J., Vollmer, J. M., O’Donnell, B. F., & Skosnik, P. D. (2012). Cannabis users differ from non-users on measures of personality and schizotypy. Psychiatry Research, 186(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2010.07.035

Gatzka, T., & Hell, B. (2018). Openness and postsecondary academic performance: A meta-analysis of facet-, aspect-, and dimension-level correlations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(3), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000194

Goel, A. D., Akarte, S. V., Agrawal, S. P., & Yadav, V. (2016). Longitudinal assessment of depression, stress, and burnout in medical students. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 7(04), 493–498. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-3147.188625

Haas, B. W., Smith, A. K., & Nishitani, S. (2018). Epigenetic Modification of OXTR is Associated with Openness to Experience. Personality Neuroscience, 1, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1017/pen.2018.7

Hammond, M. S. (2001). The Use of the Five-Factor Model of Personality as a Therapeutic Tool in Career Counseling. Journal of Career Development, 27(3), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/089484530102700302

Hoerger, M., Perry, L. M., Korotkin, B. D., Walsh, L. E., Kazan, A. S., Rogers, J. L., Atiya, W., Malhotra, S., & Gerhart, J. I. (2019). Statewide Differences in Personality Associated with Geographic Disparities in Access to Palliative Care: Findings on Openness. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 22(6), 628–634. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0206

Intiful, F. D., Oddam, E. G., Kretchy, I., & Quampah, J. (2019). Exploring the relationship between the big five personality characteristics and dietary habits among students in a Ghanaian University. BMC Psychology, 7(10), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-019-0286-z

Jackson, J. J., Hill, P. L., Payne, B. R., Parisi, J. M., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2019). Linking openness to cognitive ability in older adulthood: The role of activity diversity. Aging & Mental Health, 24(7), 1079–1087. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1655705

Jackson, J. J., Hill, P. L., Payne, B. R., Roberts, B. W., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2012). Can an old dog learn (and want to experience) new tricks? Cognitive training increases openness to experience in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 27(2), 286–292. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025918

Jokela, M., Alvergne, A., Pollet, T. V., & Lummaa, V. (2011). Reproductive behavior and personality traits of the Five Factor Model. European Journal of Personality, 25(6), 487-500. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.822

Jokela, M., Hintsanen, M., Hakulinen, C., Batty, G. D., Nabi, H., Singh-Manoux, A., & Kivimäki, M. (2013). Association of personality with the development and persistence of obesity: a meta-analysis based on individual-participant data. Obesity Reviews, 14(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12007

Jonassaint, C. R., Boyle, S. H., Williams, R. B., Mark, D. B., Siegler, I. C., & Barefoot, J. C. (2007). Facets of Openness Predict Mortality in Patients With Cardiac Disease. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(4), 319–322. https://doi.org/10.1097/psy.0b013e318052e27d

Kendler, K. S., Aggen, S. H., Gillespie, N., Neale, M. C., Knudsen, G. P., Krueger, R. F., Czajkowski, N., Ystrom, E., & Reichborn-Kjennerud, T. (2017). The Genetic and Environmental Sources of Resemblance Between Normative Personality and Personality Disorder Traits. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(2), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2016_30_251

Konrath, S., Meier, B. P., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). Development and validation of the single item trait empathy scale (SITES). Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.11.009

Lo, M.-T., Hinds, D. A., Tung, J. Y., Franz, C., Fan, C.-C., Wang, Y., Smeland, O. B., Schork, A., Holland, D., Kauppi, K., Sanyal, N., Escott-Price, V., Smith, D. J., O’Donovan, M., Stefansson, H., Bjornsdottir, G., Thorgeirsson, T. E., Stefansson, K., McEvoy, L. K., … Chen, C.-H. (2016). Genome-wide analyses for personality traits identify six genomic loci and show correlations with psychiatric disorders. Nature Genetics, 49(1), 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3736

Lüdtke, O., Roberts, B. W., Trautwein, U., & Nagy, G. (2011). A random walk down university avenue: life paths, life events, and personality trait change at the transition to university life. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(3), 620–637. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023743

McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., Terracciano, A., Parker, W. D., Mills, C. J., De Fruyt, F., & Mervielde, I. (2002). Personality trait development from age 12 to age 18: Longitudinal, cross-sectional and cross-cultural analyses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1456–1468. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1456

Miller, T. R. (1991). The Psychotherapeutic Utility of the Five-Factor Model of Personality: A Clinician’s Experience. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(3), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5703_3

Ogrodniczuk, J. S., Piper, W. E., Joyce, A. S., McCallum, M., & Rosie, J. S. (2003). NEO-Five Factor Personality Traits as Predictors of Response to Two Forms of Group Psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 53(4), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijgp.53.4.417.42832

Osborne, D., & Sibley, C. G. (2020). Does Openness to Experience predict changes in conservatism? A nine-wave longitudinal investigation into the personality roots to ideology. Journal of Research in Personality, 87, 103979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2020.103979

P, B., R, S., & Krishnan, J. (2020). The Association of Extraversion and Openness to Experience with Psychopathology in Fresh Entrants to Professional College. National Journal of Research in Community Medicine, 9(2), 42-49. Retrieved from http://journal.njrcmindia.com/index.php/njrcm/article/view/136

Phillips, K. T., Phillips, M. M., & Duck, K. D. (2018). Factors Associated With Marijuana use and Problems Among College Students in Colorado. Substance Use & Misuse, 53(3), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1341923

Pos, K., Boyette, L. L., Meijer, C. J., Koeter, M., Krabbendam, L., & de Haan, L. (2016). The effect of childhood trauma and Five-Factor Model personality traits on exposure to adult life events in patients with psychotic disorders. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 21(6), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2016.1236014

Power, R. A., & Pluess, M. (2015). Heritability estimates of the Big Five personality traits based on common genetic variants. Translational Psychiatry, 5(7), e604. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2015.96

Rahman, M. S., Guban, P., Wang, M., Melas, P. A., Forsell, Y., & Lavebratt, C. (2017). The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR) and childhood adversity are associated with the personality trait openness to experience. Psychiatry Research, 257, 322–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.07.071

Samuel, D. B., Bucher, M. A., & Suzuki, T. (2018). A Preliminary Probe of Personality Predicting Psychotherapy Outcomes: Perspectives from Therapists and Their Clients. Psychopathology, 51(2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487362

Schwaba, T., Robins, R. W., Grijalva, E., & Bleidorn, W. (2019). Does Openness to Experience matter in love and work? Domain, facet, and developmental evidence from a 24‐year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality, 87(5), 1074–1092. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12458

Takahashi, M., Shirayama, Y., Muneoka, K., Suzuki, M., Sato, K., & Hashimoto, K. (2013). Low Openness on the Revised NEO Personality Inventory as a Risk Factor for Treatment-Resistant Depression. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e71964. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071964

Terracciano, A., McCrae, R. R., Brant, L. J., & Costa, P. T., Jr (2005). Hierarchical linear modeling analyses of the NEO-PI-R scales in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Psychology and aging, 20(3), 493–506. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.493

Thiry, B. (2020). Assessing the therapeutic alliance with the five-factor model: An expert-based approach. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique, 0. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2020.01.007

Vuijk, R., Deen, M., Sizoo, B., & Arntz, A. (2018). Temperament, Character, and Personality Disorders in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 5(2), 176–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-018-0131-y

Wagner, M. T., Mithoefer, M. C., Mithoefer, A. T., MacAulay, R. K., Jerome, L., Yazar-Klosinski, B., & Doblin, R. (2017). Therapeutic effect of increased openness: Investigating mechanism of action in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(8), 967–974. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117711712